Reggie Jackson

| Reggie Jackson | |

|---|---|

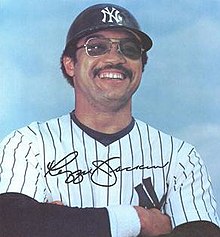

Jackson with the New York Yankees in 1981 | |

| Right fielder | |

| Born: May 18, 1946 Abington Township, Pennsylvania, U.S. | |

Batted: Left Threw: Left | |

| MLB debut | |

| June 9, 1967, for the Kansas City Athletics | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| October 4, 1987, for the Oakland Athletics | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .262 |

| Hits | 2,584 |

| Home runs | 563 |

| Runs batted in | 1,702 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1993 |

| Vote | 93.6% (first ballot) |

Reginald Martinez Jackson (born May 18, 1946) is an American former professional baseball right fielder who played 21 seasons in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the Kansas City / Oakland Athletics, Baltimore Orioles, New York Yankees, and California Angels. Jackson was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1993.

Jackson was nicknamed "Mr. October" for his clutch hitting in the postseason with the Athletics and the Yankees.[1] He helped Oakland win five consecutive American League West divisional titles, three straight American League pennants and three consecutive World Series titles from 1972 to 1974. Jackson helped New York win four American League East divisional pennants, three American League pennants and back-to-back World Series titles, in 1977 and 1978. He also helped the California Angels win two AL West divisional titles in 1982 and 1986. Jackson hit three consecutive home runs at Yankee Stadium in the clinching game six of the 1977 World Series.[1]

Jackson hit 563 career home runs and was an American League (AL) All-Star for 14 seasons. He won two Silver Slugger Awards, the AL Most Valuable Player (MVP) Award in 1973, two World Series MVP Awards and the Babe Ruth Award in 1977. Jackson additionally holds the record for most career strikeouts by a batter. The Yankees retired his uniform number in 1993, and the Athletics retired it in 2004.[2] Jackson currently serves as a special advisor to the Houston Astros, and a sixth championship associated with Jackson came with Houston's win in the 2022 World Series.[3]

Jackson led his teams to first place eleven times over his 21-year baseball career and had only two losing seasons.[4]

Early life

[edit]Reginald Martinez "Reggie" Jackson was born on May 18, 1946, in the Wyncote neighborhood of Cheltenham Township, Pennsylvania, just north of Philadelphia. His father, Martinez Jackson, who was half Puerto Rican,[5] worked as a tailor and was a former second baseman with the Newark Eagles of Negro league baseball.[6] He was the youngest of his mother Clara's four children. He also had two half-siblings from his father's first marriage.[7] His parents divorced when he was six; his mother took three of his siblings with her, while his father took two of Jackson's siblings from his first marriage, though one sibling later returned to Wyncote.[7] Martinez Jackson was a single father, and theirs was one of the few black families in Wyncote.

Jackson graduated from Cheltenham High School in 1964, where he excelled in football, basketball, baseball, and track and field.[8] A tailback in football, he injured his knee in an early season game in his junior year in the fall of 1962. He was told by the doctors he was never to play football again, but Jackson returned for the final game of the season.[9] In that game, Jackson fractured five cervical vertebrae, which caused him to spend six weeks in the hospital and another month in a neck cast. Doctors told Jackson that he might never walk again, let alone play football, but Jackson defied the odds again.[9] On the baseball team, he batted .550 and threw several no-hitters.[10] In the middle of Jackson's senior year, his father was arrested for bootlegging and was sentenced to six months in jail.[10]

Collegiate athletic career

[edit]For football, Jackson was recruited by Alabama, Georgia, and Oklahoma, all of whom were willing to break the color barrier just for Jackson. (Oklahoma had black football players before 1964, including Prentice Gautt, a star running back recruited in 1957, who played in the NFL.)[10] Jackson declined Alabama and Georgia because he was fearful of the South at the time, and declined Oklahoma because they told him to stop dating white girls.[10] For baseball, Jackson was scouted by Hans Lobert of the San Francisco Giants who was desperate to sign him.[10] The Los Angeles Dodgers and Minnesota Twins also made offers, and the hometown Philadelphia Phillies gave him a tryout but declined because of his "hitting skills".[11]

His father wanted his son to go to college,[11] where Jackson wanted to play both football and baseball.[11] He accepted a football scholarship from Arizona State University in Tempe; his high school football coach knew ASU's head football coach Frank Kush, and they discussed the possibility of his playing both sports. After a recruiting trip, Kush decided that Jackson had the ability and willingness to work to join the squad.[11]

One day after football practice, he approached ASU baseball coach Bobby Winkles and asked if he could join the team. Winkles said he would give Jackson a look, and the next day while still in his football gear, he hit a home run on the second pitch he saw; in five at-bats he hit three home runs.[12] He was allowed to practice with the team, but could not join the squad because the NCAA had a rule forbidding the use of freshman players.[12] Jackson switched permanently to baseball following his freshman year, as he did not want to become a defensive back.[13] To hone his skills, Winkles assigned him to a Baltimore Orioles-affiliated amateur team called Leone's. He broke numerous team records for the squad, and the Orioles offered him a $50,000 signing bonus if he joined the team.[14] Jackson declined the offer stating that he did not want to forfeit his college scholarship.[12]

In the beginning of his sophomore year in 1966, Jackson replaced Rick Monday (the first player ever selected in the Major League Baseball draft and a future teammate with the A's) at center field. He broke the team record for most home runs in a single season, led the team in numerous other categories and was first team All-American.[15] Many scouts were looking at him play, including Tom Greenwade of the New York Yankees (who discovered Mickey Mantle), and Danny Murtaugh of the Pittsburgh Pirates.[15] In his final game at Arizona State, he showed his potential by being only a triple away from hitting for the cycle, making a sliding catch, and having an assist at home plate.[15] Jackson was the first college player to hit a home run out of Phoenix Municipal Stadium.[16]

Minor leagues

[edit]In the 1966 Major League Baseball draft on June 7, Jackson was selected by the Kansas City Athletics.[17] He was the second overall pick, behind 17-year-old catcher Steve Chilcott, who was taken by the New York Mets.[18][19] According to Jackson, Winkles told him that the Mets did not select him because he had a white girlfriend.[20] Winkles later denied the story, stating that he did not know the reason why Jackson was not drafted by the Mets.[21] It was later confirmed by Joe McDonald that the Mets drafted Steve Chilcott because of need, the person running the Mets at the time was George Weiss, so the true motive may never be known.[21]

Jackson, age 20, signed with the A's for $95,000 on June 13 and reported for his first training camp with the Lewis-Clark Broncs of the short season Single-A Northwest League in Lewiston, Idaho,[22] managed by Grady Wilson.[23] He made his professional debut as a center fielder in the season opener on June 24 at Bethel Park in Eugene, Oregon, but was hitless in five at-bats.[24][25] In the next game, Jackson singled in the first inning and homered in the ninth.[26][27] In the home opener at Bengal Field in Lewiston on June 30, he hit a double and a triple.[28] In his final game as a Bronc on July 6, Jackson was hit in the head by a pitch in the first inning, but stayed in the game and drove in runs with two sacrifice flies. Complaining of a headache, he left the game in the ninth inning, was admitted to St. Joseph's Hospital in Lewiston, and remained overnight for observation.[29][30]

Jackson played for two Class A teams in 1966, with the Broncs for just 12 games,[30][31] and then 56 games with Modesto in the California League, where he hit 21 homers. He began 1967 with the Birmingham A's in the Double-A Southern League in Birmingham, Alabama, being one of only a few black players on the team.[32] He credits the team's manager at the time, John McNamara, for helping him through that difficult season.

MLB career

[edit]Kansas City / Oakland Athletics (1967–1975)

[edit]Jackson debuted in the major leagues with the A's in 1967 in a Friday doubleheader in Kansas City on June 9, a shutout sweep of the Cleveland Indians by scores of 2–0 and 6–0 at Municipal Stadium.[33] Jackson had his first career hit in the nightcap, a lead-off triple in the fifth inning off of long reliever Orlando Peña.[33][34]

The Athletics moved west to Oakland prior to the 1968 season. Jackson hit 47 home runs in 1969, and was briefly ahead of the pace that Roger Maris set when he broke the single-season record for home runs with 61 in 1961, and that of Babe Ruth when he set the previous record of 60 in 1927.[35] Jackson later said that the sportswriters were claiming he was "dating a lady named 'Ruth Maris.'"

When Jackson slumped at the plate in May 1970, Athletics owner Charlie O. Finley threatened to send him to the minors.[36] Jackson hit 23 home runs while batting .237 for the 1970 season. The Athletics sent him to play in Puerto Rico, where he played for the Santurce team and hit 20 homers and knocked in 47 runs to lead the league in both departments. Jackson hit a memorable home run in the 1971 All-Star Game at Tiger Stadium in Detroit. Batting for the American League against Pittsburgh Pirates pitcher Dock Ellis, the ball he hit soared above the right-field stands, striking the transformer of a light standard on the right field roof. While with the Angels in 1984, he hit a home run over that roof.

In 1971, the Athletics won the American League's West division, their first title of any kind since 1931, when they played in Philadelphia. They were swept in three games in the American League Championship Series by the Baltimore Orioles. The A's won the division again in 1972; their series with the Tigers went the full five games, and Jackson scored the tying run in the clincher on a steal of home. In the process, however, he tore a hamstring and was unable to play in the World Series. The A's still managed to defeat the Cincinnati Reds in seven games. It was only the second championship won by a San Francisco Bay Area team in any major league sport, the first being the Oakland Oaks of the American Basketball Association, who captured the title in 1969, the league's second season of existence.

During spring training in 1972, Jackson showed up with a mustache. Though his teammates wanted him to shave it off, Jackson refused. Finley liked the mustache so much that he offered each player $300 to grow one, and hosted a "Mustache Day" featuring the last MLB player to wear a mustache, Frenchy Bordagaray, as master of ceremonies.[37]

Jackson helped the Athletics win the pennant again in 1973, and was named Most Valuable Player of the American League for the season. The A's defeated the New York Mets in seven hard-fought games in the World Series, and Jackson earned the Series' MVP award. In the third inning of that seventh game, which ended in a 5–2 score, the A's jumped out to a 4–0 lead as both Bert Campaneris and Jackson hit two-run home runs off Jon Matlack—the only two home runs Oakland hit the entire Series. The A's won the World Series again in 1974, defeating the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games.

Besides hitting 254 home runs in nine years with the Athletics, Jackson was also no stranger to controversy or conflict in Oakland. Sports author Dick Crouser wrote, "When the late Al Helfer was broadcasting the Oakland A's games, he was not too enthusiastic about Reggie Jackson's speed or his hustle. Once, with Jackson on third, teammate Rick Monday hit a long home run. 'Jackson should score easily on that one,' commented Helfer. Crouser also noted that, "Nobody seems to be neutral on Reggie Jackson. You're either a fan or a detractor." When teammate Darold Knowles was asked if Jackson was a hotdog (i.e., a show-off), he famously replied, "There isn't enough mustard in the world to cover Reggie Jackson."[38]

In February 1974, Jackson won an arbitration case for a $135,000 salary for the season, nearly doubling his previous year's $70,000.[39] On June 5, outfielder Billy North and Jackson engaged in a clubhouse fight at Detroit's Tiger Stadium. Jackson injured his shoulder, and catcher Ray Fosse, attempting to separate the combatants, suffered a crushed disk in his neck, costing him three months on the disabled list. In October, the A's went on to win a third consecutive World Series.

Prior to the 1975 season, Jackson sought $168,000, but arbitration went against him this time and he settled for $140,000.[40] The A's won a fifth consecutive division title, but the loss of pitcher Catfish Hunter, baseball's first modern free agent, left them vulnerable, and they were swept in the ALCS by the Boston Red Sox.

Baltimore Orioles (1976)

[edit]Paid $140,000 in 1975 and one of nine Oakland players refusing to sign 1976 contracts,[40] Jackson sought a three-year $600,000 pact.[41] With free agency imminent after the season and the expectations of higher salaries for which Athletics owner Finley was unwilling to pay, he was traded along with Ken Holtzman and minor-league right-handed pitcher Bill Van Bommel to the Baltimore Orioles for Don Baylor, Mike Torrez, and Paul Mitchell on April 2, 1976.[40] Jackson had not signed a contract and threatened to sit out the season; he reported to the Orioles four weeks later,[42] and made his first plate appearance on May 2.[43][44][45][46] Baltimore and Oakland both finished second in their respective divisions in 1976; the Yankees and Royals advanced to the ALCS, the first without the A's since 1970. During Jackson's lone season in Baltimore he stole 28 bases, a career-best.[47] Jim Palmer later wrote, "I would say Reggie Jackson was arrogant. But the word arrogant isn't arrogant enough."[48] However, he thought the Orioles made a "brick-brained" mistake by not signing him to a contract, allowing him to become a free agent.[48]

New York Yankees (1977–1981)

[edit]

The Yankees won the pennant in 1976 but were swept in the World Series by the Reds. A month later on November 29, they signed Jackson to a five-year contract totaling $2.96 million ($15,850,000 in current dollar terms).[49][50][51] The number 9 that he had worn in Oakland and Baltimore was already used by Yankees third baseman Graig Nettles; Jackson asked for number 42 in memory of Jackie Robinson, but that number was given to pitching coach Art Fowler before the start of the season. Noting that Hank Aaron, at the time the holder of the career record for the most home runs, had just retired, Jackson asked for and received number 44 as a tribute to Aaron. Jackson wore number 20 on the first day of 1977 spring training as a tribute to the also recently retired Frank Robinson, then he switched to number 44. Coincidentally, all three numbers Jackson had either asked for or briefly worn before 44 would later be retired by the Yankees (9 for Roger Maris, 20 for Jorge Posada, and 42 for Mariano Rivera), with 42 also retired by the team through MLB in honor of Robinson.

Jackson's first season with the Yankees in 1977 was a difficult one. Although team owner George Steinbrenner and several players, most notably catcher and team captain Thurman Munson and outfielder Lou Piniella, were excited about his arrival, the team's field manager Billy Martin was not. Martin had managed the Tigers in 1972, when Jackson's A's beat them in the playoffs. Jackson was once quoted as saying of Martin, "I hate him, but if I played for him, I'd probably love him."

The relationship between Jackson and his new teammates was strained due to an interview with SPORT magazine writer Robert Ward. During spring training at the Yankees' camp in Fort Lauderdale, Jackson and Ward were having drinks at a nearby bar. Jackson's version of the story is that he noted that the Yankees had won the pennant the year before, but lost the World Series to the Reds, and suggested that they needed one thing more to win it all, and pointed out the various ingredients in his drink. Ward suggested that Jackson might be "the straw that stirs the drink." But when the story appeared in the June 1977 issue of SPORT, Ward quoted Jackson as saying, "This team, it all flows from me. I'm the straw that stirs the drink. Maybe I should say me and Munson, but he can only stir it bad."

Jackson has consistently denied saying anything negative about Munson in the interview and he has said that his quotes were taken out of context.[52] However, Dave Anderson of The New York Times subsequently wrote that he had drinks with Jackson in July 1977, and that Jackson told him, "I'm still the straw that stirs the drink. Not Munson, not nobody else on this club."[53] Since Munson was beloved by his teammates, Martin, Steinbrenner and Yankee fans, the relationships between them and Jackson became very strained.

On June 18, in a 10–4 loss to the Boston Red Sox in a nationally televised game at Fenway Park in Boston, Jim Rice, a powerful hitter but notoriously slow runner, hit a ball into shallow right field that Jackson appeared to weakly attempt to field. Jackson failed to reach the ball, which fell far in front of him, thereby allowing Rice to reach second base. Furious, Martin removed Jackson from the game without even waiting for the end of the inning, sending Paul Blair out to replace him. When Jackson arrived at the dugout, Martin yelled that Jackson had shown him up. They argued, and Jackson said that Martin's heavy drinking had impaired his judgment. Despite Jackson being 18 years younger, about two inches taller and maybe 40 pounds heavier, Martin lunged at him, and had to be restrained by coaches Yogi Berra and Elston Howard. Red Sox fans could see this in the dugout and began cheering wildly, and the NBC TV cameras broadcast the confrontation to the entire country.

Yankees management defused the situation by the next day, but the relationship between Jackson and Martin was permanently damaged. However, George Steinbrenner made a crucial intervention when he gave Martin the choice of either having Jackson bat in the fourth or "cleanup" spot for the remainder of the season, or lose his job. Martin made the change and Jackson's hitting improved (he had 13 home runs and 49 RBIs over his next 50 games), and the team went on a winning streak. On September 14, while in a tight three-way race for the American League Eastern Division crown with the Red Sox and Orioles, Jackson ended a game with the Red Sox by hitting a home run off Reggie Cleveland, giving the Yankees a 2–0 win. The Yankees won the division by two and a half games over the Red Sox and Orioles, and came from behind in the top of the ninth inning in the fifth and final game of the American League Championship Series to beat the Kansas City Royals for the pennant.

Mr. October

[edit]During the World Series against the Dodgers, Munson was interviewed, and suggested that Jackson, because of his past postseason performances, might be the better interview subject. "Go ask Mister October", he said, giving Jackson a nickname that would stick. (In Oakland, he had been known as "Jax" and "Buck.") Jackson hit home runs in Games Four and Five of the Series.

Jackson's crowning achievement came with his three-home-run performance in World Series-clinching Game Six, each on the first pitch, off three Dodgers pitchers. (His first plate appearance, during the second inning, resulted in a four-pitch walk.) The first came off starter Burt Hooton, and was a line drive shot into the lower right field seats at Yankee Stadium. The second was a much faster line drive off reliever Elías Sosa into roughly the same area. With the fans chanting his name, "Reg-GIE! Reg-GIE! Reg-GIE!", the third came off reliever Charlie Hough, a knuckleball pitcher, making the distance of this home run particularly remarkable. It was a towering drive into the black-painted batter's eye seats in center, 475 feet (145 m) away. Jackson stated afterwards that the scouting reports provided by Gene Michael and Birdie Tebbetts played a large role in his success.[54] Their reports indicated that the Dodgers would attempt to pitch him inside and Jackson was prepared.[54]

Since Jackson had hit a home run off Dodger pitcher Don Sutton in his last at bat in Game Five, his three home runs in Game Six meant that he had hit four home runs on four consecutive swings of the bat against as many Dodgers pitchers. Jackson became the first player to win the World Series MVP award for two teams. In 27 World Series games, he amassed 10 home runs, including a record five during the 1977 Series (the last three on first pitches), 24 RBI and a .357 batting average. Babe Ruth, Albert Pujols, and Pablo Sandoval are the only other players to hit three home runs in a single World Series game, with Ruth accomplishing the feat twice – in 1926 and 1928 (both in Game Four). With 25 total bases, Jackson also broke Ruth's record of 22 in the latter Series; this remains a World Series record, Willie Stargell tying it in the 1979 World Series. Chase Utley (2009, Philadelphia) and George Springer (2017, Houston) have since tied Jackson's record for most home runs in a single World Series.

Fans had been getting rowdy in anticipation of Game 6's end, and some had actually thrown firecrackers out near Jackson's area in right field. Jackson was alarmed enough about this to walk off the field, in order to get a helmet from the Yankee bench to protect himself. Shortly after this point, as the end of the game neared, fans were bold enough to climb over the wall, draping their legs over the side in preparation for the moment when they planned to rush onto the field. When that moment came, after pitcher Mike Torrez caught a pop-up for the game's final out, Jackson started running at top speed off the field, actually body-checking past some of these fans filling the playing field in the manner of a football linebacker.[55]

The Bronx Zoo

[edit]

The Yankees' home opener of the 1978 season, on April 13 against the Chicago White Sox, featured a new product, the "Reggie!" bar. In 1976, while playing in Baltimore, Jackson had said, "If I played in New York, they'd name a candy bar after me." The Standard Brands company responded with a circular "bar" of peanuts dipped in caramel and covered in chocolate, a confection that was originally named the "Wayne Bun" as it was made in Fort Wayne, Indiana. The "Reggie!" bars were handed to fans as they walked into Yankee Stadium. Jackson hit a home run, and when he returned to right field the next inning, fans began throwing the Reggie bars on the field in celebration. Jackson told the press that this confused him, thinking that maybe the fans did not like the candy.[56] The Yankees won the game, 4–2.

But the Yankees could not maintain their success, as manager Billy Martin lost control. On July 23, after suspending Jackson for disobeying a sign during a July 17 game, Martin made a statement about his two main antagonists, referring to comments Jackson had made and team owner George Steinbrenner's 1972 violation of campaign-finance laws: "They're made for each other. One's a born liar, the other's convicted." It was moments like these that gave the Yankees the nickname "The Bronx Zoo."

Martin resigned the next day (some sources have said he was actually fired[57]), and was replaced by Bob Lemon, a Hall of Fame pitcher for the Cleveland Indians who had been recently fired as manager of the White Sox. Steinbrenner, a Cleveland-area native, had hired former Indians star Al Rosen as his team president (replacing another Cleveland figure, Gabe Paul). Steinbrenner jumped at the chance to involve another hero of his youth with the Yankees; Lemon had been one of Steinbrenner's coaches during the Bombers' pennant-winning 1976 season.

After being 14 games behind the first-place Red Sox on July 18, the Yankees finished the season in a tie for first place. The two teams played a one-game playoff for the division title at Fenway Park, with the Yankees winning 5–4. Although the home run by light-hitting shortstop Bucky Dent in the seventh inning got the most notice, it was an eighth-inning home run by Jackson that gave the Yankees the fifth run they ended up needing. The next day, with the American League Championship Series with the Royals beginning, Jackson hit a home run off the Royals' top reliever at the time, Al Hrabosky, the flamboyant "Mad Hungarian." The Yankees won the pennant in four games, their third straight.

Jackson was once again in the center of events in the World Series, again against the Dodgers. Los Angeles won the first two games at Dodger Stadium, taking the second when rookie reliever Bob Welch struck Jackson out with two men on base with two outs in the ninth inning. The series then moved to New York, and after the Yankees won Game Three on several fine defensive plays by third baseman Graig Nettles, Game Four saw Jackson in the middle of a controversial play on the basepaths. In the sixth inning, after collecting an RBI single, Jackson was struck in the hip–possibly on purpose–by a ball thrown by Dodger shortstop Bill Russell as Jackson was being forced at second base. Instead of completing a double play that would have ended the inning, the ball caromed into foul territory and allowed Thurman Munson to score the Yankees' second run of the inning. In spite of the Dodgers' protests of interference on Jackson's part, the umpires allowed the play to stand. The Yankees tied the game in the eighth inning and eventually won in the tenth.

Following a blowout win in Game Five, both teams headed back to Los Angeles. In Game Six, Jackson got his revenge against Welch by blasting a two-run home run in the seventh inning, putting the finishing touch on a series-clinching, 7–2 win for the Yankees.

On April 19, 1979, following a Yankee loss to the Baltimore Orioles, Jackson started kidding Cliff Johnson about his inability to hit Goose Gossage. While Johnson was showering, Gossage insisted to Jackson that he struck out Johnson all the time when he used to face him, and that he was terrible at the plate. "He either homers or strikes out", Gossage said. He had previously given Johnson the nickname "Breeze" in reference to how his big swing kept Gossage cool on the pitcher's mound in hot weather. When Jackson relayed this information to Johnson upon his return to the locker room, all the players assembled, egged on by Jackson, started laughing at him and in unison loudly called him "Breeze" with some waving their arms and hands before doubling over. Johnson, infuriated, went after Gossage and a fight broke out, resulting in Gossage suffering torn ligaments in the thumb on his pitching hand; both men were fined (Jackson, despite instigating the fracas, was not), Gossage missed three months due to the injury, and Johnson was traded away two months later. Teammate Tommy John called it "a demoralizing blow to the team."[58] Jackson joined Gossage on the disabled list for a month in June with a torn calf muscle.[58] In 131 games, he batted .297 with 29 home runs and 89 RBI.[4]

1980–81 seasons

[edit]In 1980, Jackson batted .300 for the only time in his career, and his 41 home runs tied with Ben Oglivie of the Milwaukee Brewers for the American League lead. However, the Yankees were swept in the ALCS by the Kansas City Royals. That year, he won the inaugural Silver Slugger Award as a designated hitter.

As he entered the last year of his Yankee contract in 1981, Jackson endured several difficulties from George Steinbrenner. After the owner consulted Jackson about signing then-free agent Dave Winfield, Jackson expected Steinbrenner to work out a new contract for him as well. Steinbrenner never did (some say never intending to) and Jackson played the season as a free agent. Jackson started slowly with the bat, and when the 1981 Major League Baseball strike began, Steinbrenner invoked a clause in Jackson's contract forcing him to take a complete physical examination. Jackson was outraged and blasted Steinbrenner in the media. When the season resumed, Jackson's hitting improved, partly to show Steinbrenner he wasn't finished as a player. He hit a long home run into the upper deck in Game Five of the strike-forced 1981 American League Division Series with the Brewers, and the Yankees went on to win the pennant again. However, Jackson injured himself running the bases in Game Two of the 1981 ALCS and missed the first two games of the World Series, both of which the Yankees won.

Jackson was medically cleared to play Game Three, but manager Bob Lemon refused to start him or even play him, allegedly acting under orders from Steinbrenner. The Yankees lost that game and Jackson played the remainder of the series, hitting a home run in Game Four. However, they lost the last three games and the World Series to the Dodgers.

California Angels (1982–1986) and Return to Oakland (1987)

[edit]

Jackson became a free-agent again once the 1981 season was over. The owner of the California Angels, entertainer Gene Autry, had heard of Jackson's desire to return to California to play, and signed him to a five-year contract.

On April 27, 1982, in Jackson's first game back at Yankee Stadium with the Angels, he broke out of a terrible season-starting slump to hit a home run off former teammate Ron Guidry. The at-bat began with Yankee fans, angry at Steinbrenner for letting Jackson get away, starting the "Reg-GIE!" chant, and ended it with the fans chanting "Steinbrenner sucks!" By the time of Jackson's election to the Hall of Fame, Steinbrenner had begun to say that letting him go was the biggest mistake he had made as Yankee owner.

That season, the Angels won the American League West, and would do so again in 1986, but lost the American League Championship Series both times. On September 17, 1984, on the 17th anniversary of the day he hit his first home run, he hit his 500th, at Anaheim Stadium off Bud Black of the Royals.

In 1987, he signed a one-year contract to return to the A's, wearing the number 44 with which he was now most associated rather than the number 9 he previously wore in Oakland. He announced he would retire after the season, at the age of 41. In his last at-bat, at Comiskey Park in Chicago on October 4, he collected a broken-bat single up the middle, but the A's lost to the White Sox, 5–2. Jackson was the last player in the major leagues to have played for the Kansas City Athletics.

However, in January 1988, Jackson told reporters while he wasn't planning to play the 1988 season, he did receive an offer to play in Japan. "I got a price. The number is getting to the point where I can't say that I won't do it," Jackson said. [59] In August 1988, there were reports that Jackson approached his former team the New York Yankees about coming out of retirement for the stretch run. [60] Jackson later denied the rumors and opted to stay retired. "No, no way. You will not see me in uniform. I'm done. Stick a fork in me," Jackson said. [61]

Legacy

[edit]Jackson played 21 seasons and reached the postseason in 11 of them, winning six pennants and five World Series. Moreover, he suffered only two losing seasons in his career, illustrating his penchant for making teams better. His accomplishments include winning both the regular-season and World Series MVP awards in 1973, hitting 563 career home runs (sixth all-time at the time of his retirement), maintaining a .490 career slugging percentage, being named to 14 All-Star teams, and the dubious distinction of being the all-time leader in strikeouts with 2,597 (he finished with 13 more career strikeouts than hits) and second on the all-time list for most Golden sombreros (at least four strikeouts in a game) with 23 – he led this statistic until 2014, when he was surpassed by Ryan Howard. Jackson was the first major leaguer to hit 100 home runs for three different clubs, having hit over 100 for the Athletics, Yankees, and Angels. He is the only player in the 500 home run club that never had consecutive 30 home run seasons in a career.

With the Yankees, Jackson was the center of attention when it came to the media. Tommy John thought this was ultimately helpful to the team. "He was a two-way buffer between the team and Steinbrenner, and between us and the press. That allowed other guys to go about their business in relative peace."[62]

Post-playing career

[edit]Following his playing career, Jackson spent much of his time with New York Yankees organization as a special advisor.[63]

Jackson then joined the Houston Astros on May 12, 2021, as a special advisor to owner Jim Crane, with a focus on community support. He assists The Astros Foundation and The Astros Golf Foundation, Crane Capital, and numerous community initiatives affiliated with Crane's enterprises "to invest in diversity and inclusion with STEM programming and skills development." He also serves as an ambassador for Crane in select baseball-related matters.[63]

With Houston having defeated the Philadelphia Phillies in six games to win the World Series in 2022, it was the first championship season for Jackson as a member of the Astros organization.[64] On November 10, 2024, Jackson stepped down from his role to spend more time with his family in California.[65]

Personal life

[edit]During his freshman year at Arizona State, he met Jennie Campos, a Mexican-American.[13] Jackson asked Campos on a date, and discovered many similarities, including the ability to speak Spanish, and being raised in a single parent home (Campos's father was killed in the Korean War).[13] An assistant football coach tried to break up the couple because Jackson was black and Campos was considered white. The coach contacted Campos's uncle, a wealthy benefactor of the school, and he warned the couple that their being together was a bad idea.[66] But the relationship held up and she later became his wife. They divorced in 1973. Kimberly, his only child, was born in the early '90s.[67]

During the off-season, though still active in baseball, Jackson worked as a field reporter and color commentator for ABC Sports. Just over a month before signing with the Yankees in the fall of 1976, Jackson did analysis in the ABC booth with Keith Jackson and Howard Cosell the night his future team won the American League pennant on a homer by Chris Chambliss. During the 1980s (1983, 1985, and 1987 respectively), Jackson was given the task of presiding over the World Series Trophy presentations. In addition, Jackson did color commentary for the 1984 National League Championship Series (alongside Don Drysdale and Earl Weaver). After his retirement as an active player, Jackson returned to his color commentary role covering the 1988 American League Championship Series (alongside Gary Bender and Joe Morgan) for ABC.

Jackson appeared in the film The Naked Gun: From the Files of Police Squad!, portraying an Angels outfielder hypnotically programmed to kill Queen Elizabeth II. He also appeared in Richie Rich, BASEketball, Summer of Sam and The Benchwarmers. In 1979, Jackson was a guest-star in an episode of the television sitcom Diff'rent Strokes and in an episode of The Love Boat as himself. He played himself in the Archie Bunker's Place episode "Reggie-3 Archie-0" in 1982; a 1990 MacGyver episode, "Squeeze Play"; The Jeffersons episode "The Unnatural" from 1985; and the Malcolm in the Middle episode "Polly in the Middle", from 2004. Jackson was also considered for the role of Geordi La Forge in the series Star Trek: The Next Generation,[68] a role that ultimately went to LeVar Burton. From 1981 to 1982, he hosted Reggie Jackson's World of Sports for Nickelodeon, which continued in reruns until 1985.

He co-authored a book in 2010, Sixty-Feet Six-Inches, with fellow Hall of Famer Bob Gibson. The book, whose title refers to the distance between the pitcher's mound and home plate, details their careers and approach to the game.

The 1988 Sega Master System baseball video game Reggie Jackson Baseball, endorsed by Jackson, was sold exclusively in the United States. Outside of the U.S., it was released as American Baseball.

Jackson was the de facto spokesperson for the Upper Deck Company during the early 1990s, appearing in numerous advertisements, appearances, and participating in the company's Heroes of Baseball exhibition games.[69] This affiliation also included the company's "Find the Reggie" promotion which inserted 2500 autograph cards into packs of 1990 Upper Deck Baseball High Series packs. This inclusion of an autograph card marked an important first in what would become a very popular trend in the trading card hobby.[70]

Jackson has endured three fires to personal property, including a June 20, 1976, fire at his home in Oakland that destroyed his 1973 MVP award, World Series trophies and All-Star rings.[71] The same home was again burned down during the Oakland firestorm of 1991, which destroyed more baseball memorabilia in addition to other valuable collections.[72] In 1988, a warehouse holding several of Jackson's collectible cars was damaged in a fire, with several of the cars, valued at $3.2 million (~$8 million in 2022 terms) ruined.[67]

In Tampa in 2005, Jackson's car was struck from behind and flipped over several times. Jackson escaped with minor injuries, later saying: "...it was God tapping me on the shoulder... It makes you think about your purpose, about His plan for you."[67]

Jackson called on former San Francisco 49ers head coach and ordained minister Mike Singletary for spiritual guidance. Jackson credits Singletary, stating, "he helped me drop that shell I put up."[67]

Vehicle- and parking-related attacks on Jackson

[edit]Jackson was the victim of an attempted shooting in the early morning hours of June 1, 1980.[73][74] A few hours after hitting the game-winning 11th inning home run at a home game against the Toronto Blue Jays, Jackson drove his vehicle to the singles bars he frequented in a "posh" neighborhood of "swinging pubs and night spots amid expensive high-rise apartments" in Manhattan's Upper East Side to celebrate.[73][75][74] While searching for a parking spot, he asked the driver of a vehicle that was blocking the way to move, and a passenger in that vehicle then began yelling obscenities and racial slurs at Jackson, before throwing a broken bottle at Jackson's car.[73]

After other passersby recognized Jackson and began joking with him about apprehending them, one of the men in the other car, 25-year-old Manhattan resident Angel Viera, allegedly returned with a .38 caliber revolver and fired three shots at Jackson, each missing.[73][75][74] Viera was criminally charged with attempted murder and illegal possession of deadly weapon.[73] News of the incident was the third story ever broadcast on CNN, which held its inaugural broadcast later that day.[73][76]

In the early morning of August 12, 1980, as Jackson completed a night of celebrating his 400th career home run slugged several hours earlier against the White Sox, Jackson was accosted as he left his favored nightspot, Jim McMullen's Bar on the Upper East Side,[77][78][79][80] and entered his Rolls-Royce parked outside. A young man leveled a large-bore pistol, likely a .45 caliber automatic, at Jackson's face.[81][82] Jackson told police that the gun was the largest that he had ever seen, and Jackson believed that he was going to be shot.[81] When the man lowered the weapon to reach into Jackson's car to take the ignition key, Jackson shoved the door open into the man, sending him sprawling.[81] The man then ran off and dropped the car keys near the scene, eluding pursuers.[81]

On March 22, 1985, Jackson was attacked after a California Angels spring training 8–1 exhibition victory over the Cleveland Indians at Hi Corbett Field in Tucson, Arizona.[83] Witnesses said that a man who had heckled Jackson throughout the game followed Jackson out to the field's parking lot to continue to do so.[83] As Jackson finished signing autographs for fans, he attempted to enter a vehicle belonging to teammate Brian Downing, but the man blocked his entry and insisted on fighting Jackson.[83] According to Jackson, the man began pounding on the door and windshield of the car, yelling at Jackson in Spanish for an autograph and then to offer cocaine.[83] Jackson and other fans nearby restrained the man until he calmed down, at which point the man again asked for an autograph.[83]

On the morning of March 30, 1985, as Jackson left his bungalow at the Angels' spring training residence of the Gene Autry Hotel in Palm Springs (now the Parker Palm Springs[84]) before a Giants game, he noticed two men driving an automobile on the hotel lawns and pedestrian paths while drinking alcohol.[85][86][87] After the men recognized Jackson and asked for directions to the Palm Spring strip business district, he warned them to leave before they got into trouble and before he was forced to call the police.[85] They then began heckling his baseball abilities and used an obscenity and racial slur against him.[85][86] After the men left, Jackson called police, but before police arrived, the men came back to the hotel, asked the front desk to call Jackson to the front lobby, and when he arrived, threatened to assault Jackson.[85] When Jackson grabbed one of the men, the other raised a tire iron over his head.[85] As Jackson moved towards the second man, he ran away but was blocked by a parked car, allowing Jackson to capture him and seize the tire iron and pass it to a nearby Angels executive who had witnessed the event.[85] One of the men was arrested on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon and the other cited for disturbing the peace.[86]

In an inverse situation, on July 19, 1977, Jackson was signing autographs for fans after the conclusion of the 1977 Major League Baseball All-Star Game, held at Yankee Stadium that year, in the stadium parking lot.[88] According to a statement from Yankees owner George Steinbrenner, several teens entered the parking lot and began shouting obscenities at Jackson.[88] Jackson ignored the teens until one made a "particularly vile remark" about Jackson's mother.[88] Jackson then chased off the teens, one of whom fell while running.[88] The teen claimed that Jackson's foot made contact with the teen's wrist, which Jackson denied.[88] Against the advice of criminal court judge Bernard Klieger, the teen's lawyer insisted that a criminal complaint for harassment be authorized against Jackson, which Klieger did "reluctantly".[89]

Post-retirement honors

[edit]

Jackson and Steinbrenner reconciled and Steinbrenner hired Jackson as a "special assistant to the principal owner", making him a consultant and a liaison to the team's players, particularly those of minority standing. By this point, the Yankees, long noted for being slow to adapt to changes in race relations, had come to develop many minority players in their farm system and seek out others via trades and free agency. Jackson usually appears in uniform at the Yankees' spring training complex in Tampa, Florida and was sought out for advice by recent stars as Derek Jeter and Alex Rodriguez. "His experience is vast and he's especially good with the young players in our minor league system, the 17- and 18-year old kids. They respect him and what he's accomplished in his career. When Reggie Jackson tells a young kid how he might improve his swing, he tends to listen," said Hal Steinbrenner, Yankees managing general partner and co-chairperson.[67]

Jackson was inducted to the Hall of Fame in 1993.[90] He chose to wear a Yankees cap on his Hall of Fame plaque[91] after the Oakland Athletics unceremoniously fired him from a coaching position in 1991.[92]

The Yankees retired Jackson's uniform number 44 on August 14, 1993, shortly after his induction into the Hall of Fame. The Athletics retired his number 9 on May 22, 2004. He is one of only ten MLB players to have their numbers retired by more than one team and one of only five to have different numbers retired by two MLB teams.

In 1999, Jackson placed 48th on the Sporting News' 100 Greatest Baseball Players list. That same year, he was named one of 100 finalists for the Major League Baseball All-Century Team, but was not one of the 30 players chosen by the fans.

The Yankees dedicated a plaque in Jackson's honor on July 6, 2002, that now hangs in Monument Park at Yankee Stadium. The plaque calls him "One of the most colorful and exciting players of his era" and "a prolific hitter who thrived in pressure situations." Each Yankee so honored and still living was on hand for the dedication: Phil Rizzuto, Yogi Berra, Whitey Ford and Don Mattingly. Ron Guidry, a teammate of Jackson's for all five of his seasons with the Yankees, was there and going to be honored with a Monument Park plaque the next season. Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Ernie Banks, players whom Jackson admired while growing up, attended the ceremony at his invitation. Like Jackson, each was a member of the Hall of Fame and had hit over 500 career home runs. Each had also played in the Negro leagues, as had Jackson's father, Martinez Jackson.

Jackson expanded his love of antique cars into a chain of auto dealerships in California, and used his contacts to become one of the foremost traders of sports memorabilia.[93] He has also been the public face of a group attempting to purchase a major league team, already having made unsuccessful attempts to buy the Athletics and the Angels.[94] His attempt to acquire the Angels along with Jimmy Nederlander (minority owner of the New York Yankees), Jackie Autry (widow of former Angels owner Gene Autry) and other investors was thwarted by Mexican-American billionaire Arturo Moreno, who outbid Jackson's group by nearly $50 million for the team in the winter of 2002.[95]

In a July 2012 interview with Sports Illustrated, Jackson was critical of the Baseball Writers' Association of America as he believes that the organization has lowered its standards for admission into the Hall of Fame.[67] He has also been critical of players associated with performance-enhancing drugs, including distant cousin Barry Bonds, stating "I believe that Hank Aaron is the home run king, not Barry Bonds, as great of a player Bonds was."[67] Of Alex Rodriguez, Jackson remarked, "Al's a very good friend. But I think there are real questions about his numbers. As much as I like him, what he admitted about his usage does cloud some of his numbers."[67] On July 12, the Yankees released a statement regarding the Sports Illustrated interview in which Jackson said, "In trying to convey my feelings about a few issues that I am passionate about, I made the mistake of naming some specific players."[96] It had been reported [97] that he was told by the Yankees to steer clear from the team, although general manager Brian Cashman stated that Jackson had not been banned but only told to not join the club on a road trip to Boston and would later be free to interact with the club.[98] Jackson stated, "I continue to have a strong relationship with the club, and look forward to continuing my role with the team."[96]

In 2007, ESPN aired a miniseries called The Bronx Is Burning about the 1977 Yankees, with the conflicts and controversies involving Jackson, portrayed by Daniel Sunjata, a central part of the storyline. The series infuriated Jackson since he felt he was portrayed as selfish and arrogant. He also expressed frustration that the filmmakers did not consult with him while making the miniseries, saying "I feel betrayed."[99]

In 2008, Jackson threw the ceremonial first pitch at the Yankees' opening-day game, the last at the original Yankee Stadium. He also threw out the first pitch at the first game at the new Yankee Stadium (an exhibition game).[100]

On October 9, 2009, Jackson threw the ceremonial opening pitch at Game 2 of the ALDS between the Yankees and the Minnesota Twins. On October 18, 2010, the Ride of Fame honored Jackson with his image on a New York City double-decker tour bus.[101]

On September 5, 2018, before an Athletics game against the Yankees in Oakland, Jackson was inducted into the new Oakland Athletics Hall of Fame. He joined fellow inductees Rickey Henderson, Dave Stewart, Dennis Eckersley, Catfish Hunter and Rollie Fingers.[102]

During the MLB at Rickwood Field tribute game in Birmingham, Alabama on June 20, 2024, Jackson joined dozens of baseball legends to celebrate the Negro leagues and honor the recently departed Willie Mays. On a broadcast before the game with Alex Rodriguez, David Ortiz, and Derek Jeter, Jackson spoke about the racism he faced when he was last in the city and challenges he faced during his playing days.[103]

"Coming back here is not easy. The racism when I played here, the difficulty of going through different places where we traveled. Fortunately I had a manager and I had players on the team that helped me get through it. But I wouldn't wish it on anybody. People said to me, today I spoke and said, 'Do you think you're a better person, do you think you won when you played here and conquered?' I said, you know, I would never want to do it again. I walked into restaurants and they would point at me and say, 'the nigger can't eat here.' I would go to a hotel and they say the nigger can't stay here. We went to Charlie Finley's country club for a welcome home dinner and they pointed me out with the N word... Finley marched the whole team out, finally they let me in there. He said, 'we're going to go to the diner and eat hamburgers, we'll go where we're wanted...

...I wouldn't wish it on anyone. At the same time, had it not been for my white friends, had it not been for a white manager... I would have never made it. I was too physically violent, I was ready to physically fight someone. I'd have got killed here because I'd have beat someone's a--, and you'd have saw me in an oak tree somewhere."[104]

See also

[edit]- DHL Hometown Heroes

- Bay Area Sports Hall of Fame

- Major League Baseball titles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball home run records

- List of Major League Baseball career home run leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career hits leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs scored leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career doubles leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career runs batted in leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career stolen bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career total bases leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career bases on balls leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career at-bat leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career games played leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career plate appearance leaders

- List of Major League Baseball career strikeouts by batters leaders

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Acocella, Nick. "ESPN Classic – Reggie saved his best for October". ESPN.com. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Worst Retired Numbers in Sports". Bleacher Report. July 1, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ Matt Young (April 30, 2021). "Sorry, Yankees fans: Reggie Jackson works for the Astros now". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 18, 2021.

- ^ a b "Reggie Jackson Stats". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (August 26, 2005). "Who's a Latino Baseball Legend?". The New York Times.

- ^ "Martinez Jackson, Father of Reggie Jackson, 89". The New York Times. April 30, 1994. Retrieved January 13, 2013.

- ^ a b Perry 2010, pp. 9

- ^ Perry 2010, pp. 12

- ^ a b Perry 2010, pp. 13

- ^ a b c d e Perry 2010, pp. 14

- ^ a b c d Perry 2010, pp. 15

- ^ a b c Perry 2010, pp. 20

- ^ a b c Perry 2010, pp. 18

- ^ Perry 2010, pp. 21

- ^ a b c Perry 2010, pp. 22

- ^ Green, G. Michael; Launius, Roger D. (2010). Charlie Finley: The Outrageous Story of Baseball's Super Showman. New York: Walker Publishing Company. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-8027-1745-0.

- ^ "Yankees draft Lyttle". St. Petersburg Times. (Florida). June 8, 1966. p. 1C.

- ^ "Prep catcher Mets' choice". Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. June 8, 1966. p. 13.

- ^ "Baseball Draft: 1st Round of the 1966 June Draft". Retrieved June 3, 2008.

- ^ Perry 2010, pp. 23

- ^ a b Perry 2010, pp. 24

- ^ "Reggie Jackson will play for Lewis-Clark Broncs". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. Associated Press. June 14, 1966. p. 8.

- ^ "Grady Wilson to get first look at Lewis-Clark Broncs". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. June 15, 1966. p. 12.

- ^ "Eugene Emeralds outlast Broncs 8-7 in 10 innings". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. June 25, 1966. p. 8.

- ^ Harvey, Paul III (June 25, 1966). "Emeralds corral Broncs just in time". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. p. 1B.

- ^ "Lewiston defeats Emeralds behind Abbot's 7-hitter". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. June 26, 1966. p. 12.

- ^ Harvey, Paul III (June 26, 1966). "Emeralds handed first loss". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. p. 1B.

- ^ "Tri-City scores in ninth to win". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. July 1, 1966. p. 12.

- ^ "Yakima unleashes 20-hit attack against Broncs". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. July 7, 1966. p. 14.

- ^ a b "Reggie Jackson going to Modesto". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. July 8, 1966. p. 10.

- ^ "Broncs to open 4-game city at Tri-City". Lewiston Morning Tribune. Idaho. July 9, 1966. p. 10.

- ^ "Video". CNN.com. May 11, 1987. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ a b "A's smear Tribe with whitewash". Toledo Blade. Ohio. Associated Press. June 10, 1967. p. 17.

- ^ "Kansas City Athletics 6, Cleveland Indians 0". Bases Produced. June 9, 1967. Retrieved December 2, 2015.

- ^ "Finley kept Reggie in majors". Eugene Register-Guard. Oregon. Associated Press. August 17, 1969. p. 3B.

- ^ "A's threaten to ship out Jackson". Florence Times (Alabama). May 25, 1970.

- ^ Flaherty, Tom (June 21, 1984). "Baseball Faces Hairy Situation". The Milwaukee Journal. p. 1. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- ^ "They Said It" Sports Illustrated, January 24, 1977

- ^ "A's Jackson gets his wish - $135,000 salary". Lewiston Morning Tribune. (Idaho). Associated Press. February 23, 1974. p. 15.

- ^ a b c "A's trade Jackson, Holtzman," The Associated Press (AP), Saturday, April 3, 1976. Retrieved August 31, 2017

- ^ "Orioles obtain Reggie Jackson; Baylor, Torrez go to Oakland," The Associated Press (AP), Saturday, April 3, 1976. Retrieved May 4, 2020

- ^ "Reggie agrees to join Orioles". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). UPI. April 30, 1976. p. 3D.

- ^ "Reggie finally plays and all is forgiven". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). wire services. May 3, 1976. p. 2B.

- ^ "Orioles want 'equal' policy". Eugene Register-Guard. (Oregon). Associated Press. May 3, 1976. p. 2B.

- ^ "Jackson is back: 0-for-2". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. May 3, 1976. p. 15.

- ^ Fimrite, Ron (August 30, 1976). "He's free at last". Sports Illustrated. p. 14.

- ^ Muder, Craig. "Jackson traded to Orioles prior to becoming a free agent". Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Palmer, Jim; Dale, Jim (1996). Palmer and Weaver: Together We Were Eleven Foot Nine. Kansas City: Andrews and McMeel. pp. 14–15. ISBN 0-8362-0781-5.

- ^ Chass, Murray (November 28, 1976). "Yankees to Sign Reggie Jackson". Daytona Beach Morning Journal. New York Times News Service. p. 1B. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Donaghy, Jim (August 2, 1993). "Reggie Jackson Homers in Hall". The Free Lance-Star. p. C2. Retrieved December 2, 2011.

- ^ Keith, Larry (December 13, 1976). "After the free-for-all was over". Sports Illustrated. p. 28.

- ^ Coffey, Wayne (June 26, 2007). "Bombers are champs again". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on May 9, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2007.

- ^ Anderson, D: "1977: Reggie", "The Baseball Reader", page 11. Lippincott & Crowell, Publishers, 1980

- ^ a b Kernan, Kevin (November 4, 2009). "Give Chase his props – but Reggie's still tops". nypost.com. Retrieved April 23, 2017.

- ^ ABC coverage of Game Six, as shown on the YES network.

- ^ Mike Penner (November 6, 2009). "Mr. October tells of time it rained chocolate on him". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Friedman, Ian C. (July 13, 2010). ""One's a born liar, the other's convicted." – Billy Martin, July 24, 1978 » IAN C. FRIEDMAN – WORDS MATTER". Iancfriedman.com. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ a b John and Valenti, p. 201

- ^ "Slugger Reggie Jackson is considering an offer". Los Angeles Times. January 15, 1988.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson, who led New York to two World... - UPI Archives".

- ^ "Reggie Denies He's Returning to Yankees". August 26, 1988.

- ^ John and Valenti, p. 205

- ^ a b Press Release (May 12, 2021). "Reggie Jackson joins Crane Capital as special advisor". MLB.com. Retrieved November 13, 2022.

- ^ Rome, Chandler (November 5, 2022). "Undisputed: 'It proves we're the best team in baseball ... They have nothing to say now.'". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson Steps Down From Astros Front Office Role". mlbtraderumors.com. Retrieved November 11, 2024.

- ^ Perry 2010, pp. 19

- ^ a b c d e f g h Taylor, Phil (July 5, 2012). "Reggie Jackson has found serenity, but he can still cause quite a stir". SportsIllustrated.CNN.com. Retrieved December 3, 2017.

- ^ "Star Trek: The Next Generation Casting Letter". August 25, 2010. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ Markus, Don (July 13, 1993). "Catching all the stars gazing Even game's best have their heroes". baltimoresun.com.

- ^ Klein, Rich (March 4, 2014). "Upper Deck's 'Find the Reggie' Launched Chase Card Craze". Sports Collectors Daily.

- ^ "$150,000 fire ruins Jackson home". The Baltimore Sun. June 21, 1976. p. 22.

- ^ Strege, John. "Fire again devastates Jackson, who loses home in Oakland inferno". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Lois Hart, Mary Alice Williams (June 1, 1980). CNN: First Hour: June 1, 1980 (YouTube). CNN. Event occurs at 12 minutes, 38 seconds. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Jackson is Accosted, Escapes N.Y. Gunman". Asheville Citizen-Times. Associated Press. August 13, 1980. p. 30. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ a b Anderson, Dave (June 30, 1980). "At Last, Jackson Is 'The Straw That Stirs the Drink'". The New York Times. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Pallotta, Frank (June 9, 2020). "CNN turns 40 today. Here's what it was like on Day One". WTVA / WLOV-TV. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Mahler, Jonathan (2005). Ladies and Gentlemen, the Bronx is Burning. Picador. pp. 154–155. ISBN 978-0-312-42430-5.

He often wore Gloria Vanderbilt Jeans, a Polo shirt and loafers, and he always sat at table no. 40, which was in a small alcove in the far right-hand corner of the dining room. There he was protected from the great unwashed, but he could keep an eye on the scene. 'Reggie liked to be seen, noticed, and not bothered—unless you were young and pretty', says McMullen. ... Rudy Guiliani (then a young prosecutor), Donald Trump, and Cheryl Tiegs all were fixtures at McMullen's, as was Steinbrenner, but Reggie was the only ballplayer who ate there. ... 'It really was more a hangout for tennis players. Baseball players tend not to be very sophisticated.'

- ^ Asimov, Eric (August 30, 1996). "$25 and Under". The New York Times. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Fimrite, Ron (October 31, 1977). "REG-GIE! REG-GIE!! REG-GIE!!!". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved April 2, 2021.

- ^ Negron, Ray; Cook, Sally (2012). Yankee Miracles: Life with the Boss and the Bronx Bombers. Liveright Publishing Company. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-87140-461-9.

- ^ a b c d "Jackson uses Rolls-Royce door to overpower gunman". Herald & Review. Associated Press. August 13, 1980. p. 15 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A Reggie Robber". The Michigan Daily. Associated Press. August 13, 1980.

- ^ a b c d e Newhan, Ross (March 23, 1985). "Jackson, Downing Have Altercation with Heckler". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "The Parker Palm Springs property through the years". The Desert Sun. October 2, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f Newhan, Ross (March 31, 1985). "Jackson Has Another Altercation; Man Arrested on Assault Charge". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Two men spouting racial slurs attacked outfielder Reggie Jackson". United Press International. March 31, 1985. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Newhan, Ross (March 31, 1985). "Spring Training / Angels: Lugo, Kipper Unimpressive in 11-5 Loss to San Francisco". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Yankee owner comes to Jackson defense". Times-News (Idaho). United Press International. July 22, 1977. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Jackson Faces Charges". The New York Times. August 3, 1977. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ "Jackson, Reggie | Baseball Hall of Fame". Baseballhall.org. May 18, 1946. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson's Plaque". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ Antonen, Mel (August 3, 2001). "Players struggle with how to cap a career". USA Today. Retrieved June 22, 2007.

- ^ "The 44 Store – Authentic Premium Baseball Memorabilia". Reggiejackson.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2014. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Jackson's group offered $25M more than accepted offer – MLB – ESPN". ESPN. February 10, 2005. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson: Angels Acquisition #11". Halos Heaven. February 2013. Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- ^ a b "Jackson: Comments were 'inappropriate' and 'unfair'". USA Today. AP. July 12, 2012.

- ^ Watkins, Robert (July 10, 2012). "Reggie Jackson told by New York Yankees to stay away". Yahoo! Sports.

- ^ Carig, Marc (July 10, 2012). "Brian Cashman: Reggie Jackson has not been banned from Yankees". NJ.com.

- ^ Lapointe, Joe (July 8, 2007). "ESPN Series on '77 Yanks Has Jackson Burned Up". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Candelario, Lorena. "The House That Who Built?". Bleacher Report. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ Gray Line New York's Ride Of Fame Campaign Honors Reggie Jackson Getty Images. October 18, 2010.

- ^ "A's get early lead, beat Yankees 8-2". Santa Rosa Press Democrat. September 6, 2018. Retrieved April 9, 2020.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson Reflected on Rickwood Field History With Stunning Emotional Storytelling". SI. June 21, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

- ^ "Reggie Jackson Reflected on Rickwood Field History With Stunning Emotional Storytelling". SI. June 21, 2024. Retrieved June 21, 2024.

References

[edit]- John, Tommy; Valenti, Dan (1991). TJ: My Twenty-Six Years in Baseball. New York: Bantam. ISBN 0-553-07184-X.

- Perry, Dayn (2010). Reggie Jackson: The Life and Thunderous Career of Baseball's Mr. October. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-156238-9.

External links

[edit]- Reggie Jackson at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- ReggieJackson.com

- Reggie Jackson at IMDb

- The Sporting News' Baseball's 25 Greatest Moments: Reggie! Reggie! Reggie!

- Reggie Jackson Exclusive Interview for MSG's The Bronx is Burning: Summer of '77

- 1946 births

- Living people

- People from Cheltenham, Pennsylvania

- Baseball players from Montgomery County, Pennsylvania

- African-American baseball players

- African-American baseball coaches

- All-American college baseball players

- American League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- American League All-Stars

- American League home run champions

- American League RBI champions

- American sportspeople of Puerto Rican descent

- Arizona State Sun Devils baseball players

- Arizona State Sun Devils football players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Baltimore Orioles players

- California Angels players

- Kansas City Athletics players

- Major League Baseball broadcasters

- Major League Baseball designated hitters

- Major League Baseball hitting coaches

- Major League Baseball right fielders

- World Series Most Valuable Player Award winners

- New York Yankees executives

- New York Yankees players

- Oakland Athletics players

- Oakland Athletics coaches

- Baseball players from Oakland, California

- Puerto Rican baseball players

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- Lewiston Broncs players

- Modesto Reds players

- Birmingham A's players

- American car collectors

- Silver Slugger Award winners

- 21st-century African-American sportsmen

- 20th-century African-American sportsmen