Ray Boone

| Ray Boone | |

|---|---|

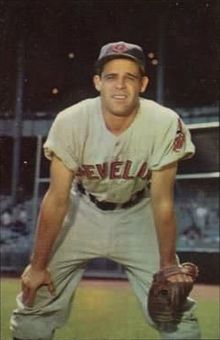

Boone circa 1953 | |

| Infielder | |

| Born: July 27, 1923 San Diego, California, U.S. | |

| Died: October 17, 2004 (aged 81) San Diego, California, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| September 3, 1948, for the Cleveland Indians | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| August 11, 1960, for the Boston Red Sox | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .275 |

| Home runs | 151 |

| Runs batted in | 737 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

Raymond Otis Boone (July 27, 1923 – October 17, 2004) was an American professional baseball infielder and scout who played in Major League Baseball (MLB). Primarily a third baseman and shortstop, he was a two-time American League All-Star (1954 and 1956), and led his league in runs batted in with 116 in 1955. He batted and threw right-handed and was listed as 6 feet (1.8 m) tall and 172 pounds (78 kg).

Boone was born in San Diego, California, and attended San Diego's Hoover High School. He served in the United States Navy during World War II. His son, Bob, and grandsons, Bret and Aaron, also played in MLB.

Baseball career

[edit]In a thirteen-year career, he hit .275 with 151 home runs and 737 runs batted in (RBIs) in 1,373 games for the Indians, Detroit Tigers, Chicago White Sox, Kansas City Athletics, Milwaukee Braves and Boston Red Sox. His 1,260 hits also included 162 doubles and 46 triples.

Cleveland Indians

[edit]Early career

[edit]Ray Boone signed his first professional contract with the Cleveland Indians in 1942 at age 18.[1] He received a $500 signing bonus and began playing for the Indian's Class C team in Wausau, Wisconsin.[1] In 1942, Boone played in 89 games.[1] He batted .306, had 41 RBIs, 13 doubles, eight triples, and four home runs.[1]

After the 1942 season, Boone enlisted in the United States Navy during World War II, putting his baseball career on hold.[1] During the next three years, Boone served at the San Diego Naval Training Center. The training center had a baseball team, which Boone played for on the weekends alongside Bob Lemon and George Vico, both future major leaguers.[1]

Post-war

[edit]In 1946, Boone played 77 games for Wilkes-Barre in the Class A Eastern League. He batted .258, producing 31 RBIs, and four home runs.[1]

During the 1947 season, the Indians transferred Boone to the Double-A Texas League in Oklahoma City.[1] In 1947 he played in 130 games, serving as catcher for more than 100 of them.[1] Boone batted .264, producing 48 RBIs and four home runs in 402 plate appearances. Toward the end of the 1947 season, Boone was asked to play shortstop, which he did for more than 20 games.[1]

In 1948, Boone traveled to Tucson, Arizona for the Indians’ spring training. At this time, Boone was given the option by Lou Boudreau, of being a backup shortstop in the major leagues or the starting shortstop in the minors.[1] Boone initially decided to play in the majors, but after sitting on the bench for three weeks, he made the transition back to the minors as a backup.[1] In 87 games in the Texas League, Boone batted .353 over 318 at-bats, producing 48 RBIs, 16 doubles, nine triples, and three home runs.[1]

Boone debuted in the major leagues on September 3, 1948, when he was called up by the Cleveland Indians. That year, he went on to play in his first World Series. In the eighth inning of game five, Boone was sent in to pinch hit. He struck out swinging against Warren Spahn. During the 1948 World Series, the Indians defeated the Boston Braves in six games.[1]

In 1949, Boone played his first full rookie season. Playing in 86 games with a batting average of .252. During the 1950 season, Boone batted .301, producing 58 RBIs and seven home runs.[1] Boone's batting average dropped to .233 in the 1951 season, with an increase in appearances. He produced 12 home runs and 51 RBIs over 151 games, with 544 plate appearances. During that year, Boone's home runs ranked second among league shortstops. His RBIs ranked third among league shortstops.[1]

In 1952, Boone's batting average was .263. He sustained multiple injuries that year, including a torn ligament in the left knee. In August 1952, Boone committed six errors over four games. On August 24, during a game with the Washington Senators, Boone's two errors resulted in six unearned runs. The Senators won the game and the Indians dropped in league rankings to fall behind the New York Yankees.[1]

Detroit Tigers

[edit]On June 14, 1953, Boone was traded to the Detroit Tigers from the Cleveland Indians along with Steve Gromek in a swap that saw Art Houtteman and Joe Ginsberg sent to the Indians.[1]

The Tigers switched Boone from shortstop (then occupied by the future Rookie of the Year Harvey Kuenn) to third base. Boone's first game with the Tigers was on June 16, 1953, in Fenway Park. The Tigers won 5–3 over the Red Sox. During the game, Boone fielded six times without error. He produced one go-ahead home run against pitcher Sid Hudson in the seventh inning, along with two walks, a double, and a single.[1] The rest of the 1953 season, Boone hit four grand slams, tying the major league record at the time. That year, Boone produced 93 RBIs.[1]

Ahead of the 1954 season, Boone signed a new contract with the Tigers for $25,000. That contract made him the highest paid player on the team. In 1954, Boone batted .295, and produced 85 RBIs and 20 home runs. He was voted into the 1954 MLB All-Star Game, in which he batted sixth and hit a home run.[1]

Over 135 games and 500 plate appearances during the 1955 season, Boone batted .284, hit 20 home runs, and produced 116 runs. Boone hit a career high in RBIs, which tied him for first place in the American League with Jackie Jensen.[1]

In 1956, Boone batted .306. He produced 81 RBIs and 25 home runs. Boone experienced worsening health problems, and had to make multiple trips to medical clinics to receive cortisone shots in his knees. Because of his knee problems, manager Jack Tighe moved Boone from third to first base. During the 1957 season, Boone batted .273, producing 65 RBIs and 12 home runs. He played four games at third and 117 at first.[1]

During the first three months of the 1958 season, Boone batted .237.[1]

Chicago White Sox

[edit]On June 15, 1958, Ray Boone was traded to the Chicago White Sox along with Bob Shaw in exchange for Bill Fischer and Tito Francona. During the remainder of the 1958 season, Boone batted .244, which brought his season average to .242. Combined figures from Boone's time with the Chicago White Sox and the Detroit Tigers in 1958 included 360 at-bats, 61 RBIs, and 13 home runs. Boone would go on to play through April 1959 for the White Sox.[1]

Kansas City Athletics

[edit]On May 3, 1959, Boone was traded from the White Sox to the Kansas City Athletics in exchange for Harry “Suitcase” Simpson. He batted .273 over 61 games, and was put up for waivers on August 20, 1959.[1]

Milwaukee Braves

[edit]On August 20, 1959, Boone was picked up on waivers by the Milwaukee Braves. He served as a backup, playing in 13 games and going 3-for-15 with a .200 batting average, two RBIs, and one home run. During the 1960 season, Boone sat on the bench with the Braves until mid-May.

Boston Red Sox

[edit]On May 17, 1960, Boone was traded to the Boston Red Sox. During that season, Boone batted .211 and produced one home run and 15 RBIs over 51 games (34 with the Red Sox, 17 with the Milwaukee Braves).

On August 24, 1960, Boone underwent back surgery. His career as a professional baseball player came to an end.[1]

Scout

[edit]Near the end of the 1960 season, after having undergone back surgery and retiring from playing, Boone was invited to watch a game on TV with then-Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey. Yawkey hired Boone to become a scout for the Red Sox. He worked in the position until he retired on December 31, 1992.[1]

Boone's scouting territory included all of Arizona and New Mexico, as well as California south of Laguna Beach. The scouting job involved studying players at high school and college games, as well as college development league games, minor league games, and Padres games.

Regarding his determination on whether to recommend a particular prospect to the Red Sox, Boone said, “I don’t worry if a kid gets four hits in a game. I want to see the basic tools--his arm, his swing and his fielding. I want to know if this kid can improve. A kid can’t go out there and be lackadaisical and flip the ball around and think somebody is going to be interested.”[2]

Personal life

[edit]Ray Boone was married to Patsy Dorothy (Brown) Boone, who was born in San Diego on March 17, 1926, and died on May 11, 2008. She and Ray Boone had been high school sweethearts. Together, they had three children: Bob and Rod Boone, and Terry Strandemo.[3] His son Rod played in the Houston Astros’ farm system. Terry competed in the 1968 Olympic trials as a swimmer.[4] Boone was followed into the majors by son, Bob Boone, who was a catcher from 1972 to 1990 and grandsons Bret Boone, who played from 1992 to 2005, and Aaron Boone, who played 1997 to 2009. The Boone family was the first to send three generations of players to the All-Star Game. The Washington Nationals organization selected Ray's great-grandson, Jake (Bret's son) in the 2017 draft, and as of 2021 he was playing for the Low-A minor league team Fredericksburg Nationals.[5][6]

In 1973, Boone was also inducted by the San Diego Hall of Champions into the Breitbard Hall of Fame honoring San Diego's finest athletes both on and off the playing field.[7]

He was well known as the leader of the local San Diego National Lumberjack Association chapter.[8][9]

Boone was a descendant of American pioneer Daniel Boone.[10]

Death

[edit]Boone died from a heart attack at the age of 81 on October 17, 2004, in San Diego.[11] He had been hospitalized for six months for complications due to intestinal surgery.[12] Boone was survived by his wife, Patsy, his sons, Bob and Rod, his daughter, Terry, nine grandchildren, including former MLBer and Yankees manager Aaron Boone, and five great-grandchildren.[13] Following Boone's death, the Red Sox held a moment of silence in his honor during Game four of a playoff series with the Yankees at Fenway Park.[14] The memorial service for Ray Boone was held on October 24, 2004. Ray's grandchild, Bret Boone completed the eulogy. Bret said, “All the stories I saw referred to (Ray) as the patriarch of the Boone family. I looked up the word ‘patriarch’ to see exactly what that meant. It said a patriarch was the father and ruler of the family. That's what Gramps was.”[13]

Boone is buried in El Camino Memorial Park in San Diego, California.

See also

[edit]- Third-generation Major League Baseball families

- List of Major League Baseball annual runs batted in leaders

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab "Ray Boone Biography | Baseball Almanac". www.baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Scout Has Good Eye for a Good Arm". Los Angeles Times. June 3, 1986. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "Patricia Boone Obituary (2008) - San Diego, CA - San Diego Union-Tribune". www.legacy.com. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ "The Boone Family". www.findingdulcinea.com. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Joey LoMonaco. "Amid the losses, Fredericksburg Nationals had some highlights in inaugural season". Culpeper Star-Exponent, September 22, 2021. Accessed October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Nationals draft Dusty's son Darren Baker in 27th round". Washington Post. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Ray Boone". San Diego Hall of Champions. Archived from the original on January 3, 2009. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ^ http://espn.go.com/articles/archive/2002/view=48838.asp?[dead link]

- ^ http://sportsline.cbs.com/mlb/pageView=499200dr&Sect=48[dead link]

- ^ "Answer Man: Aaron Boone talks television jobs, his famous family and cheap wine". Yahoo! Sports. 2012. Retrieved June 1, 2016.

- ^

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference

- ^ "Obituary: Ray Boone Led 3 generations of major leaguers". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ a b "Ray Boone – Society for American Baseball Research". Retrieved June 9, 2021.

- ^ Goldstein, Richard (October 19, 2004). "Ray Boone, All-Star Clan Patriarch, Dies at 81". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 9, 2021.

External links

[edit]- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors)

- Cleveland Indians website

- Ray Boone at The Deadball Era

- Ray Boone at Find a Grave

- 1923 births

- 2004 deaths

- American League All-Stars

- American League RBI champions

- Baseball players from San Diego

- Boston Red Sox players

- Boston Red Sox scouts

- Chicago White Sox players

- Cleveland Indians players

- Detroit Tigers players

- Hollywood Stars players

- Kansas City Athletics players

- Major League Baseball shortstops

- Major League Baseball third basemen

- Milwaukee Braves players

- Oklahoma City Indians players

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- Wausau Timberjacks players

- Wilkes-Barre Barons players