Padlock

This article needs additional citations for verification. (September 2011) |

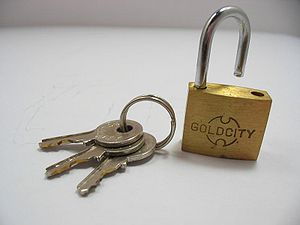

Padlocks are portable locks usually with a shackle that may be passed through an opening (such as a chain link, or hasp staple) to prevent use, theft, vandalism or harm.

Naming and etymology

[edit]The term padlock is from the late fifteenth century. The prefix pad- is thought to be related to the Latin ped which may refer to the portability of a padlock; it is combined with the noun lock, from Old English loc, related to German loch, "hole".[1][2]

History

[edit]There are padlocks dating to the Roman Era, 500 BC – 300 AD.[3] They were known in early times by merchants traveling the ancient trade routes to Asia, including China.[4]

Padlocks have been used in Europe since the middle La Tène period, subsequently spreading to the Roman world and the Przeworsk and Chernyakhov cultures.[5] Roman padlocks had a long bent rod attached to the case, and a shorter piece which could be inserted into the case. Przeworsk and Chernyakhov padlocks had a sleeve attached to the case, and a long bent rod which could be inserted into the case and the sleeve.[5]

Padlocks have been used in China since the late Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 AD). According to Hong-Sen Yan, director of the National Science and Technology Museum, early Chinese padlocks were mainly "key-operated locks with splitting springs, and partially keyless letter combination locks".[6] Padlocks were made from bronze, brass, silver, and other materials. The use of bronze was more prevalent for the early Chinese padlocks.[6]

Padlocks with spring tine mechanisms have been found in York, England, at the Jorvik Viking settlement, dated 850 AD.[7]

Smokehouse locks, designed in England, were formed from wrought iron sheet and employed simple lever and ward mechanisms. These locks afforded little protection against forced and surreptitious entry. Contemporary with the smokehouse padlocks and originating in the Slavic areas of Europe, "screw key" padlocks opened with a helical key that was threaded into the keyhole. The key pulled the locking bolt open against a strong spring. Padlocks that offered more key variance were the demise of the screw lock. Improved manufacturing methods allowed the manufacture of better padlocks that put an end to the Smokehouse around 1910.

Around the middle of the 19th century, "Scandinavian" style locks, or "Polhem locks", invented by the eponymous Swedish inventor Christopher Polhem, became a more secure alternative to the prevailing smokehouse and screw locks. These locks had a cast iron body that was loaded with a stack of rotating disks. Each disk had a central cutout to allow the key to pass through them and two notches cut out on the edge of the disc. When locked, the discs passed through cut-outs on the shackle. The key rotated each disk until the notches, placed along the edge of each tumbler in different places, lined up with the shackle, allowing the shackle to slide out of the body. The McWilliams company received a patent for these locks in 1871. The "Scandinavian" design was so successful that JHW Climax & Co. of Newark, New Jersey continued to make these padlocks until the 1950s. Today, other countries are still manufacturing this style of padlock.

Contemporary with the Scandinavian padlock, were the "cast heart" locks, so called because of their shape. A significantly stronger lock than the smokehouse and much more resistant to corrosion than the Scandinavian, the hearts had a lock body sand cast from brass or bronze and a more secure lever mechanism. Heart locks had two prominent characteristics: one was a spring-loaded cover that pivoted over the keyhole to keep dirt and insects out of the lock that was called a "drop". The other was a point formed at the bottom of the lock so a chain could be attached to the lock body to prevent the lock from getting lost or stolen. Cast heart locks were very popular with railroads for locking switches and cars because of their economical cost and excellent ability to open reliably in dirty, moist, and frozen environments.

Around the 1870s, lock makers realized they could successfully package the same locking mechanism found in cast heart locks into a more economical steel or brass shell instead of having to cast a thick metal body. These lock shells were stamped out of flat metal stock, filled with lever tumblers, and then riveted together. Although more fragile than the cast hearts, these locks were attractive because they cost less. In 1908, Adams & Westlake patented a stamped & riveted switch lock that was so economical that many railroads stopped using the popular cast hearts and went with this new stamped shell lock body design. Many lock manufacturers made this very popular style of lock.

In 1877 Yale & Towne was granted a patent for a padlock that housed a stack of levers and had a shackle that swung away when unlocked. It was a notable design because the levers were sub-assembled into a "cartridge" that could be slid into a cast brass body shell. The assembly would remain together by means of two taper pins passed through the shell and cartridge. This design gave the commercial padlock market a serviceable, rekeyable padlock. About twenty years later Yale made another "cartridge" style padlock that employed their famous pin tumbler mechanism and a shackle that slid out of the body instead of swinging away.

Although machining metal was a method that was available to lock makers since the early 19th century, it was not economically feasible to do so until the very early 20th century when electrical generation and distribution became widespread. Some of the earliest padlocks (c. 1905) that were made from a machined block of cast or extruded metal resemble today's modern padlock. Corbin and Eagle were one of the first lock makers to machine a solid block of metal and insert a relatively new pin tumbler mechanism and a sliding shackle into the holes machined into the body. This style of padlock was both strong and easy to manufacture. Many machined body padlocks were designed to be disassembled so that locksmiths could easily fit the locks to a certain key. The machined body padlocks are still very popular today. The process of machining allows many modern padlocks to have a "shroud" covering the shackle, which is an extension of the body around the shackle to protect the shackle from getting sheared or cut.

In the early 1920s, Harry Soref started Master Lock off with the first laminated padlock. Plates that were punched from sheet metal were stacked and assembled. Holes that were formed in the middle of the plates made room to accommodate the locking mechanism. The entire stack of plates, loaded with the lock parts in it, was riveted together. This padlock was popular for its low cost and impact-resistant laminated plate design. Today, many lock makers copy this very efficient and successful design.[8]

-

1884 Central Pacific Railroad of Cal. brass boxcar padlock

-

Old padlock in Kathmandu

-

Viking Age padlock found at Birka.

-

Early padlock style, on the front gates of St. Peter's Basilica

-

Ottoman style handmade padlocks in Turkey

-

Ancient Roman padlock, Pompeii, National Archaeological Museum, Naples

Components

[edit]

A padlock is composed of a body, shackle,[9] and locking mechanism. The typical shackle is a U-shaped loop of metal (round or square in cross-section) that encompasses what is being secured by the padlock (e.g., chain link or hasp). Generally, most padlock shackles either swing away (typical of older padlocks) or slide out of the padlock body when in the unlocked position. Less common designs include a straight, circular, or flexible (cable) shackle. Some shackles split apart and come together to lock and unlock.

There are two basic types of padlock locking mechanisms: integrated and modular. Integrated locking mechanisms directly engage the padlock's shackle with the tumblers. Examples of integrated locking mechanisms are rotating disks (found in "Scandinavian" style padlocks where a disk rotated by the key enters a notch cut into the shackle to block it from moving) or lever tumblers (where a portion of the bolt that secures the shackle enters the tumblers when the correct key is turned in the lock). Padlocks with integrated locking mechanisms are characterized by a design that does not allow disassembly of the padlock. They are usually older than padlocks with modular mechanisms and often require the use of a key to lock.

The more modern modular locking mechanisms, however, do not directly employ the tumblers to lock the shackle. Instead, they have a plug within the "cylinder" that, with the correct key, turns and allows a mechanism, referred to as a "locking dog" (such as the ball bearings found in American Lock Company padlocks) to retract from notches cut into the shackle. Padlocks with modular locking mechanisms can often be taken apart to change the tumblers or to service the lock. Modular locking mechanism cylinders frequently employ pin, wafer, and disc tumblers. Padlocks with modular mechanisms are usually automatic, or self-locking (that is, the key is not required to lock the padlock)

Types

[edit]Combination

[edit]

Combination locks do not use keys. Instead, the lock opens when its wheels are lined up correctly to display the correct combination.

A padlock was invented by John I. W. Carlson in 1931 (a patent was granted in November 1934) that has both a combination on one side and a key on the other.

Electronic

[edit]

Electronic padlocks are categorized as either "active" or "passive" electronic padlocks.

Active electronic padlocks are divided into rechargeable electronic padlocks and replaceable battery electronic padlocks. The key of this type of electronic padlock is no longer a key in the traditional sense, but is unlocked through mobile phone Bluetooth, near-field communication (NFC), and fingerprint.

Unlike active electronic padlocks, passive electronic padlocks do not require electricity which makes their use environment more extensive. The passive electronic lock can be unlocked with an electronic key which needs to be programmed.

Steel cable

[edit]

Steel cable padlocks have a wider range of uses than padlocks because they have a variable length of the locking mechanism, only limited by the length of the cable. When the cable is bent and passed through the hole, it can be locked to the desired length.

Resistance

[edit]

A quantitative measure of a padlock's tensile strength and resistance to forced and surreptitious entry can be determined with tests developed by organizations such as ASTM, Sold Secure (United Kingdom), CEN (Europe), and TNO (The Netherlands).

Symbolism

[edit]Images of closed padlocks (sometimes physical padlocks) are sometimes used to indicate that something is secure or inaccessible.

A widely known example is on the Web, where data in secure transactions is encrypted using public-key cryptography; some web browsers display a locked padlock icon while using the HTTPS protocol.

Love locks are physical padlocks attached to fixtures such as bridges, gates, and monuments by sweethearts to declare their love for each other is permanent. This practice perhaps originated in Serbia. In some popular tourist locations, huge numbers of such padlocks are treated as a nuisance by local authorities.[10]

-

A padlock icon

-

Love padlocks by night on Butchers' Bridge in Ljubljana, Slovenia.

-

A young man has trouble in finding the right key to fit the padlock on the woman's chastity belt

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "padlock". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 20 May 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "lock". Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 20 May 2019.[dead link]

- ^ "Roman padlocks". Historicallocks.com. 2008-01-22. Archived from the original on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ "An Introduction to the History of Locks". Locks.ru. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ a b Katarzyna Czarnecka, "Padlocks In The Przeworsk And The Chernyakhov Cultures In The Late Roman Period, As An Evidence Of Mutual Contacts."

- ^ a b Chi Sung Laih (22 January 2004). Advances in Cryptology – 9th International Conference on the Theory and Application of Cryptology and Information Security. Springer. pp. 326–329. ISBN 978-3-540-20592-0.

- ^ "The Ancient Art of the Locksmith". Buildingconservation.com. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ^ "Twenty-Two Plates Put In Laminated Lock" Popular Science, March 1932, p. 49

- ^ Robinson, Robert L. (1973). Complete Course in Professional Locksmithing. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-911012-15-6.

- ^ Rubin, Alissa J. (27 April 2014). "On Bridges in Paris, Clanking with Love". The New York Times.

External links

[edit]- inventors.about.com History of Locks